Today marks an impressive watershed for Australia’s energy transition. The coal-fired furnaces at the Liddell Power Station in New South Wales will be switched off, for good.

There are quite a few reasons for Liddell’s closure. But it has been highly controversial. The plant is more than 50 years old, and reports are that it has been running at well short of its 2 gigawatt (GW) of capacity for some years from its four 500 MW turbines.

The development is undoubtedly a good thing for Australia’s carbon emissions and it is the continuation of a trend that will not be reversed. Despite its age and the cost to its owner AGL to maintain, Liddell is also being increasingly pushed out of the market by clean energy – namely solar and wind.

Aussie homes and businesses are adopting rooftop solar and home batteries at record-setting rates, and utility scale solar and wind projects continue to be built. This means that the old coal-fired clunkers that have powered the country for decades are becoming financially uncompetitive as there are fewer and fewer opportunities for them to earn their keep. The result is they get switched off and exit the National Energy Market (NEM), and that means lower emissions.

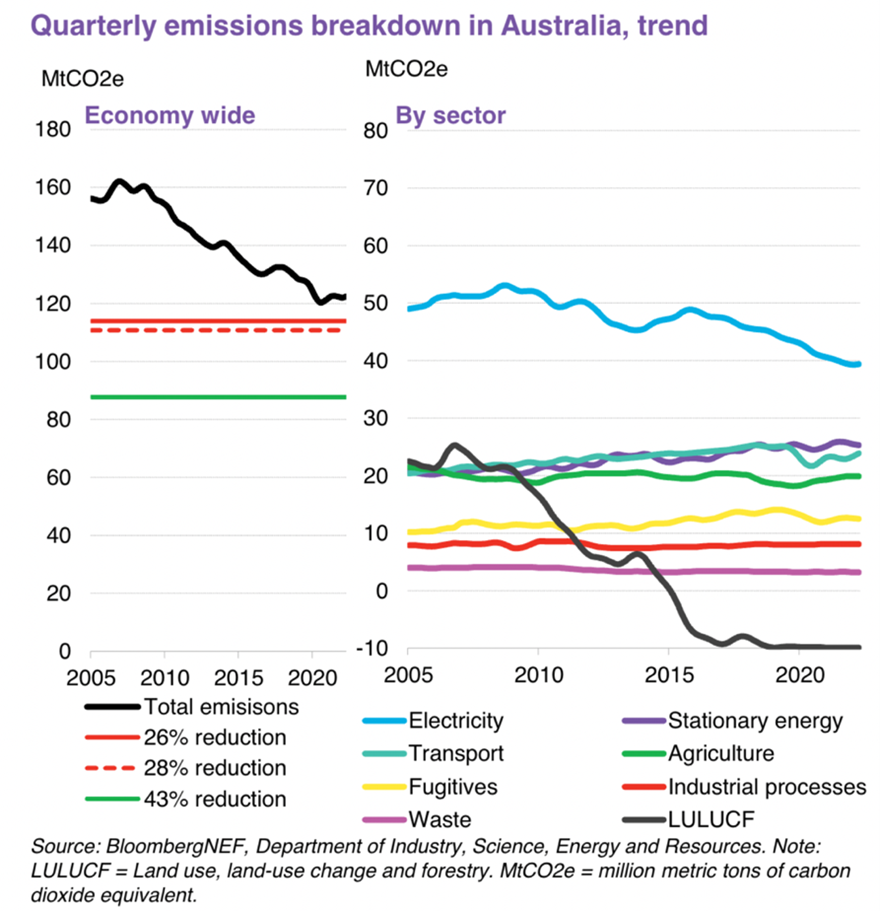

As the analysts from BloombergNEF wrote in their Australian market outlook and energy market analysis from January, retiring coal generators means dramatically reducing climate emissions from Australia’s power sector. Or, in analyst speak: “The sheer magnitude of coal generation and its precipitous decline are indicators for the fall in carbon intensity in Australia as well as the pace of decarbonisation.” Indeed.

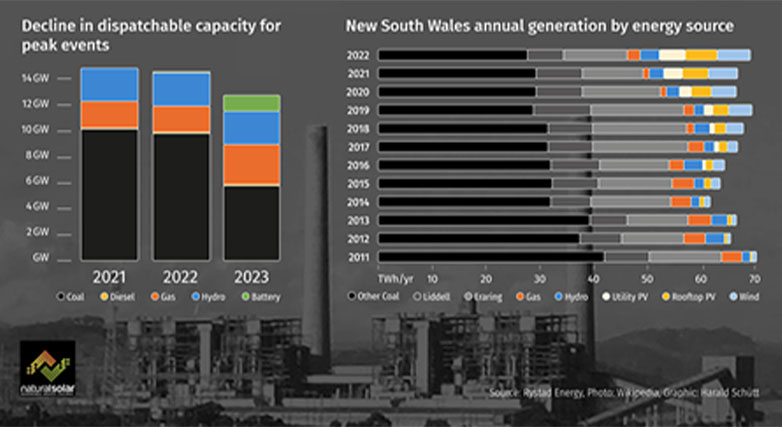

The chart below paints the picture. Our carbon emissions are falling, but it is in electricity generation where the biggest declines have been made – and the fall of “king coal” is the primary cause.

However, in the same breath Bloomberg notes that the closure of the coal generators is “transforming the energy mix in the NEM”. And this is potentially where dark clouds lurk behind the closure of Liddell’s silver lining.

Dispatchable generation

If you take a closer look at what Liddell being switched off means for Australian homes and businesses, there are a few worrying signs. The exit of Liddell and other coal generators has been anything but orderly.

The back-and-forth of energy policy under a series of federal Coalition governments has made it difficult for AGL and others to make the plans they really needed to: mothball their old coal power plants sooner rather than later. The former CEO of AGL, Andrew Vesey lost his job over his plans to shut down Liddell and replace it with solar, wind, and batteries due to a political standoff with the Coalition government at the time. And let’s not forget Malcolm Turnbull himself, who couldn’t bring his colleagues in the federal Liberal and National parties into line behind an energy policy and found himself replaced as PM by Scott Morrison.

The result of all this chaos is that there are serious concerns that the NEM, and New South Wales in particular, won’t have sufficient dispatchable power particularly in moments of light wind and darker days. While solar and wind has surged to replace the fading coal generators, these sources are variable and cannot be cranked up precisely when and where they are needed.

David Dixon, a Sydney-based renewables analyst for Rystad Energy says that we shouldn’t be short of generating capacity – particular with rooftop solar and residential battery storage being installed in so many Aussie homes. But there are concerns that there could be shortfall of “dispatchable” energy sources, particularly on hot days when air conditioners get cranked up as people try to beat the heat.

“Dispatchable capacity feels too close for comfort,” says Dixon, “especially if there is an unplanned outage at one of the four remaining coal fired power plants during a peak period – a hot summer evening or cold winter evening.”

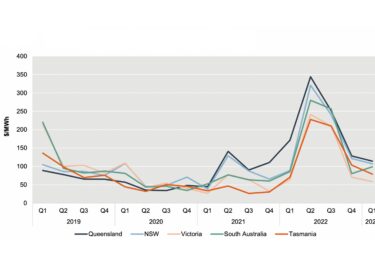

Prices set to rise (again)

There are also warning signs for electricity prices as well. With less dispatchable coal ready to plug the gaps, gas generators will be relied on. And as we know all too well, gas prices have been off the charts since Russia invaded Ukraine.

“We expect prices to rise post-Liddell as gas or hydro set the price more of the time in New South Wales, with less coal in the system. The key question is how high will gas prices go? Particularly in winter when gas demand is high,” says Dixon.

As Dixon notes, hydropower is a dispatchable source of renewable energy. And there have been two significant pumped hydro storage projects launched to bolster supply as coal departs. However, delays have struck key projects. Dixon notes that Snowy 2.0, ex-PM Turnbull’s pet project, has seen its completion delayed from the end of 2026 to 2027. And a Kurri Kurri development has also been pushed back to December 2024.

The bottom line of the new post-Liddell world is that while renewables are rising to the challenge, the chaotic way this stage of energy transition has been managed is leaving a lot to be desired.

It has been a bit of mantra of mine in 2023, but it is truer today with Liddell’s closing than ever before: Rooftop solar and home batteries is the best way for Aussie households and small businesses to take power into their own hands, have control over their prices, and, by doing so, plug the gap left by the departing coal clunkers.

It’s a good thing that coal is going the way of the dinosaurs. Now is the time for distributed and rooftop PV, made dispatchable through residential battery storage, to step up and fill the void.